Overwhelmed by climate change? Welcome to Greenprint - the place where we try to simplify all things climate and share musings on tackling our warming world.

If you haven’t subscribed, please consider joining (for free!):

Too long; didn’t read (tl;dr) 😴

Agriculture accounts for ~11.7% of global emissions. This includes

Farm-gate emissions, driven by livestock and treatment of crops

Land-use change emissions, driven by deforestation and land burning for agriculture

Pre and post-production (or ‘PPP’) emissions, including everything from farm ‘gates’ to our tables (i.e., processing, manufacturing, transport and treatment of food)

Solutions for farm-gate and land-use emissions include smarter farming methods and restoring land. Businesses and consumers can also impact ‘PPP’ emissions by making food in cleaner ways, green and local food choices and cutting down on food waste

The numbers 🔢

10%: Agriculture’s contribution to the global economy, sustaining billions of livelihoods worldwide

12%: Agriculture’s contribution towards GHG emissions

30-40%: The amount of food we make that we waste

50%: Emissions generated within the farm, as a proportion of the whole agriculture system

Agriculture finds itself in the crosshairs of climate debate and not without reason.

Its environmental footprint on deforestation, biodiversity loss and water use is undeniable – if it were a country, agriculture would be the third largest emitter behind China and the US. Even more alarming is the 30-40% figure of food produced and wasted annually across the world, with developed countries driving the lion’s share of this waste (McKinsey & Company, 2022).

As it has been for millennia, agriculture remains a vital economic engine - it sustains~10% of our global GDP today and the livelihood for millions in regions reliant on agricultural practices. However, as the global population climbs towards a projected 9.7bn by 2050, it’s clear that we need to embrace new ways of plating things up.

1. How is agriculture the second-largest emitting sector in the world?

It’s the second largest emitting sector in the world after energy, accounting for over 11.7% global emissions.

There are many ways to quantify, explain (and debate) it, but let’s use the UN Food & Agriculture Organisation’s split of the agrifood system for now:

Farm-gate emissions (48% agrifood emissions)

As the name suggests, this refers to emissions generated directly within the four walls (or fences) of farms and properties.

This includes:

a. Livestock (~55% farm-gate emissions) - the primary driver of farm-gate emissions from livestock is methane (CH4) emitted during digestion, along with nitrous oxide (N2O) from manure management.

b. Crops (~20% farm-gate emissions) - this includes fertiliser use (particularly nitrogen-based ones) and associated N2O emissions

C. Other farm-related emissions (~25% farm-gate emissions) - this might include energy use from machinery and transportation, the impacts of fires for land clearing or agricultural burning

Land-use change (19% agrifood emissions)

Land-use change emissions refer to emissions resulting from converting natural ecosystems (e.g., forests, wetlands) into agricultural land.

This includes:

a. Deforestation (~97% land use change emissions) - as forests are cleared, carbon stored in trees and soil is released into the atmosphere

b. Fires (3% land use change emissions) - fires used in land-clearing and other agricultural practices contribute less compared to deforestation, but also release carbon through combustion processes

Pre and post-production emissions (33% agrifood emissions)

This entails:

a. Packaging, transport and retail (30% PPP emissions) - per the handle, emissions from packaging materials, transportation and retail operations

b. Manufacturing of inputs and food processing (26% PPP emissions) - includes manufacturing of fertilisers as well as food, both of which are very energy-intensive

c. Household consumption (21% PPP emissions) - cooking, storing and handling food by yours truly

d. Waste disposal (22% PPP emissions) - as the name suggests. This occurs at virtually every stage of the food system. The World Bank estimates a 50% cut of this could lower emissions by 3.3GTCO2eq p.a. (that’s roughly 75,000X round-the-world trips in terms of flight emissions)

2. What’s the fix?

Let’s look at those 3 buckets again.

How do we reduce farm-gate emissions?

There’s no silver bullet, but a mix of smarter farming practices, tech, and consumer behaviour shifts can make a dent in farm-gate emissions.

Take smarter farming practices for example:

Regenerative agricultural practices such as cover cropping, no-till farming and rotational grazing can restore soil health and lock carbon into the ground. Regenerative agriculture practices could help sequester 1.2 gigatons of CO2 p.a. - the equivalent of 250 million flights from Melbourne to Perth!

Developing and using next-gen fertilisers such as green ammonia, precision fertilisers and organic alternatives can dramatically reduce nitrous oxide (NO2) emitted, in comparison to conventional fertilisers. This could drive a step-change in crop-related emissions, as NO2 is roughly 300x more potent than CO₂.

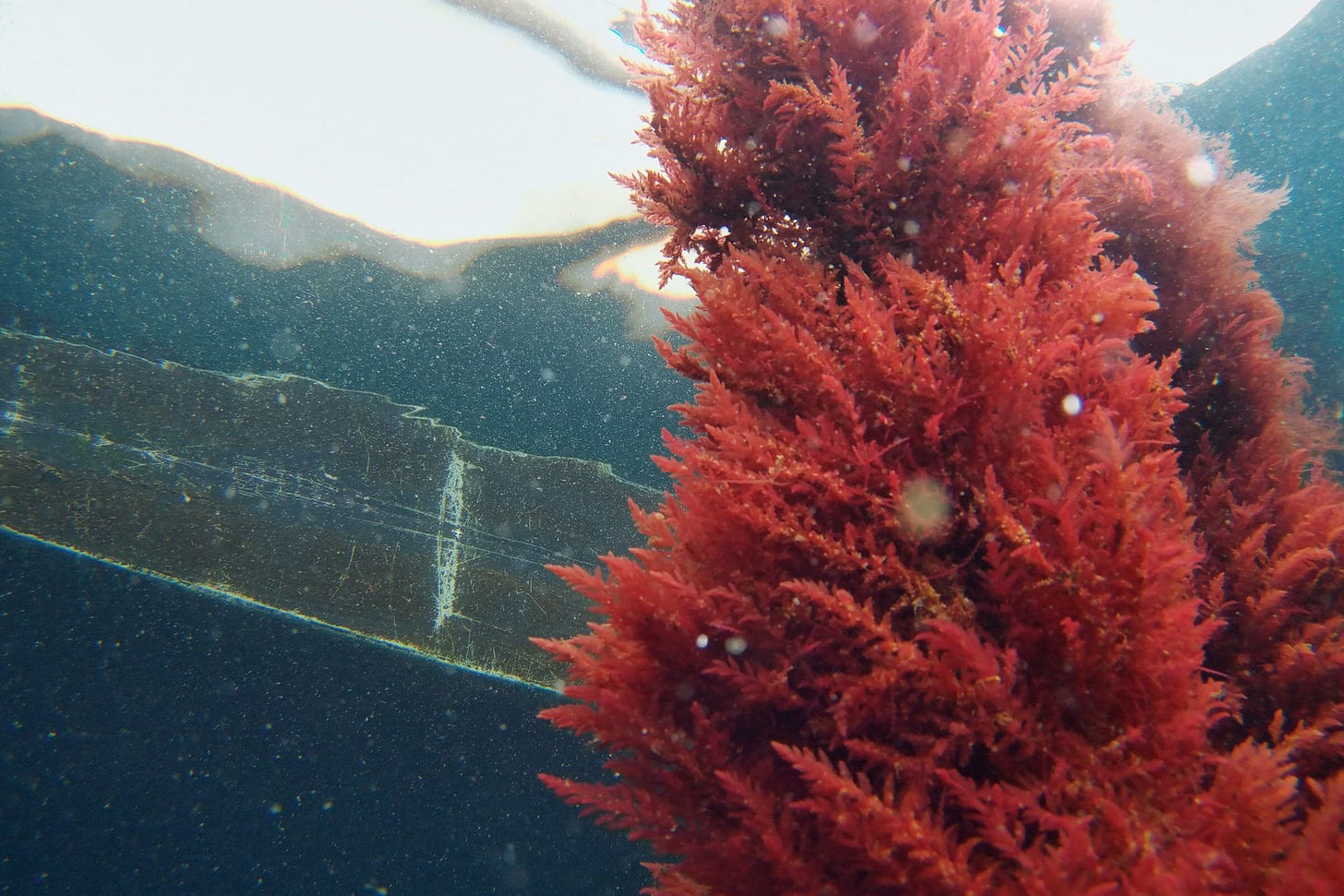

New feedstock innovations, like adding certain types of seaweed or using feed additives like 3-NOP, are showing real potential in cutting livestock’s methane emissions. These solutions work with just small amounts of feed, plus they’re scalable and easy to transport. DSM’s Bovaer, for example, is already approved in places like Brazil, Chile, and the EU, helping reduce livestock-related emissions. While there are still regulatory challenges, these technologies could make a big difference in lowering methane emissions.

Australian start-up Seaforest cultivates production of a red seaweed that, when added to livestock diets, reduces methane emissions.

Not deforesting is a no-brainer, so what else?

While land-use change related solutions can overlap with farm-gate (i.e., agricultural expansion), the key here is focusing on scaling ‘nature-based’ (NBS) solutions to regenerate land and boost carbon capture.

Nature-based solutions entail everything from:

Reforestation and afforestation - planting trees, restoring forests

Wetland restoration - reintroducing native vegetation, reconnecting wetlands to rivers and streams, restoring wetland soil

Soil nutrition improvements - applying bio-fertilisers and microbial treatments to help soil store carbon better

Agro-forestry - adding trees and shrubs to agricultural land

3. And everything else between the farm to the table?

A lot happens before food hits your plate - from packaging, transport to food waste. So much so, that 30-40% what we produce is lost.

Again - pretty straight forward:

Improving packaging and transport, such as using greener transport or temperature-controlled systems to reduce spoilage en route

Supporting ‘ugly’ fruits and vegetables - pushing inclusivity in the shapes and sizes of produce allowed to grace the supermarket shelves

Curating your plate - shifting towards a plant-based diet can support up to 50% reductions in food-related emissions

Finishing what’s on your plate - or tossing it in the compost bin

3. Who’s responsible, for what?

Nothing groundbreaking, on governments, businesses and consumers

Farms don’t operate in isolation — co-ordination across policies, markets, and consumers demand all play a role in shifting these systems towards more sustainable practices.

A simple flavour of how each stakeholder can contribute as follows:

• Stronger incentives, by governments - some exist, but not at the scale required to drive the scale or transformation needed. Subsidies, tax breaks and R&D funding can close the cost barrier that stands between using current and innovative technologies.

• Greater pressure across the supply chain, by businesses - major food companies—think Nestlé, Unilever, Walmart—are pushing to cut their emissions, and they’re looking at their suppliers. By prioritising sustainable sourcing and pushing for greener production methods, companies can help drive the pace of our transition to more sustainable agricultural practices

• Greater demand for sustainable food, by consumers - this one’s been written to the ground, but consumer purchasing power is very real. Our decisions to purchase seasonal, local and plant-based products can help reduce food-related emissions by up to 50% and clearly signal to businesses to prioritise climate friendly practices.

Melbourne-based ‘Wonki’ partners with local suppliers to source ‘wonky’ looking, but perfectly edible fruits from landfills for the production of their seltzers.

4. What does this practically look like over the next 10 years?

There a few moving parts - scaling up existing sustainable practices and integrating innovation across the food production and supply chain, and aligning both private and public incentives to make sustainable farming the norm.

For consumers, this means making mindful food choices. Adopting seasonal and greener plates can support up to 50% in food-related emissions - lowering the demand for food transport and livestock-related cultivation.

For farmers, it means navigating new incentives and innovations.

And for policymakers and businesses, it means investing in solutions that reduce emissions without compromising food production.